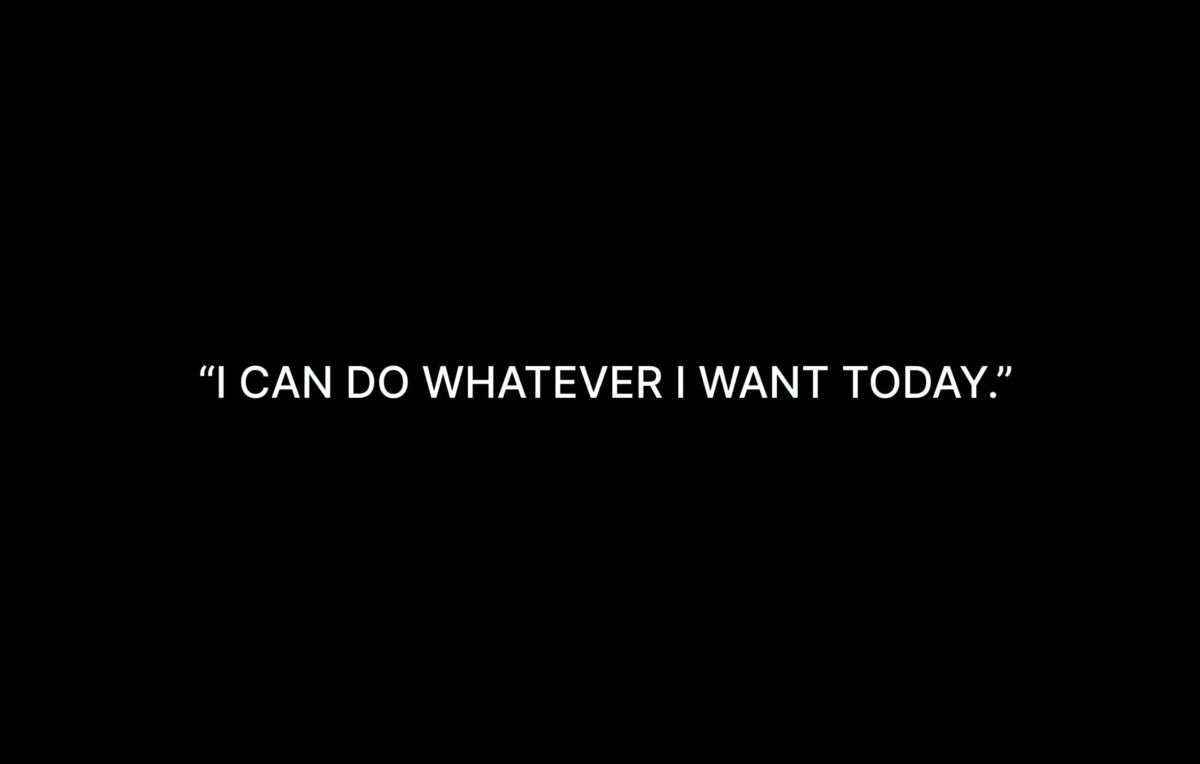

Sprinkling quotations into your writing is a very effective way to improve it. Doing this serves a number of functions.

- Quotations summarize a point you’re making in your work.

- They also emphasize this point.

- A quotation by someone both famous and respected gives confirmation to your ideas.

- They serve to break up large blocks of text.

Choosing Quotations

I’ve found that the most effective way to find quotes is to search for a topic. For example, if I want a quote from a successful woman entrepreneur, I use that term and put “quotations” in front of it. A number of sites come up, and I scroll through them.

I need to know what I’m looking for before I start reading them. I pick out several that come the closest to my goal for a suitable quote and compare them.

Several factors influence my decision.

How long is the quote? A one-sentence quote is ideal, two sentences if it really makes the point. If it’s any longer, it begins to diverge into something that looks more like text.

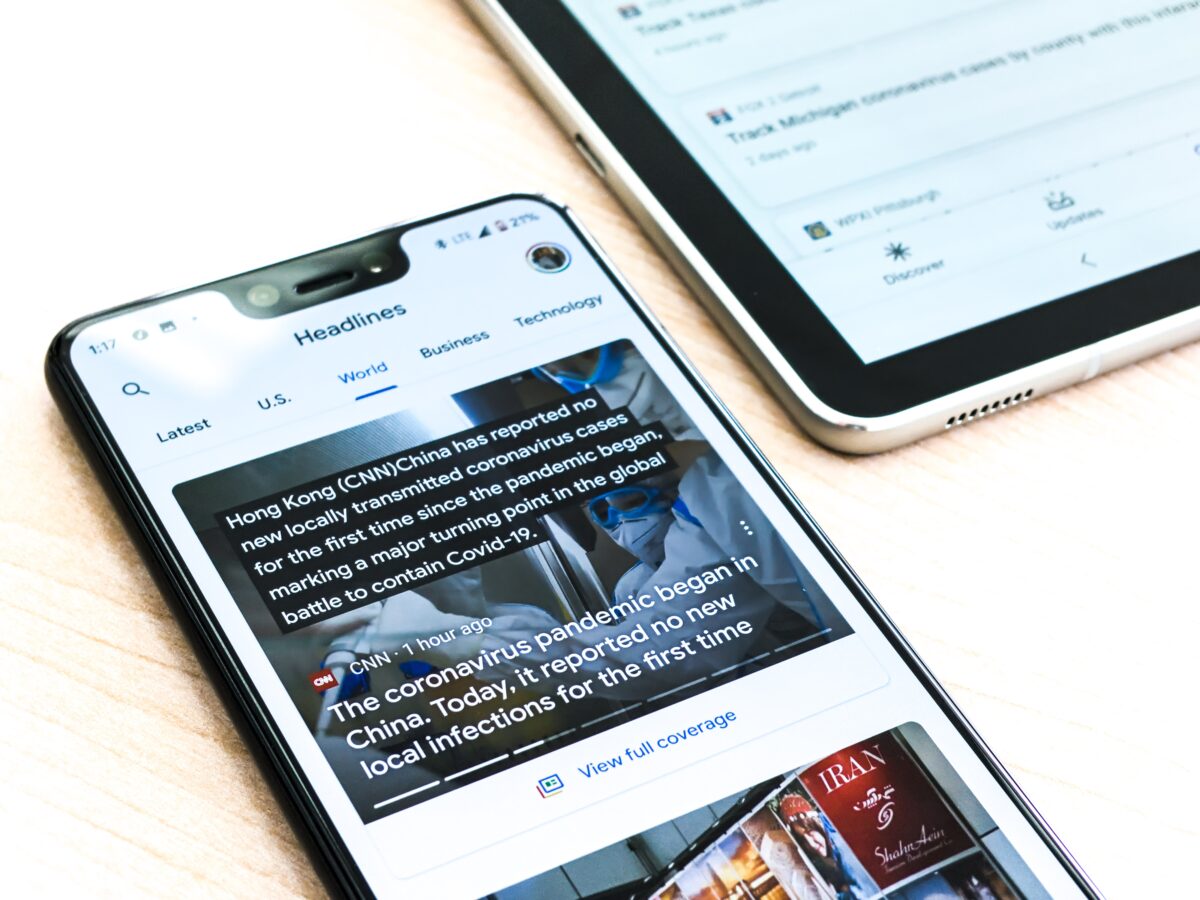

Is it accurate? Random House copyeditor Benjamin Dreyer points out in the hilarious Dreyer’s English the need to verify quotes are accurate. He cites three sources for verifying or debunking quotes:

- Wikiquote.com

- Books.google.com

- quoteinvestigator.com

Who said it? I tend not to use quotations by “Anonymous.” They may sound great, but they lack the additional clout of name familiarity.

I usually don’t use quotes by anyone I’ve never heard of. They have the same lack-of-clout problem. However, bearing in mind that I’m not swimming in the mainstream of popular culture, if the quote really has an impact, I may look the person up. If he or she is well-known, I’ll use it.

Sometimes the person’s name isn’t well-known, but her company is. For example, Debbi Fields is the founder of the Mrs. Fields company. If I saw a powerful quote by her, I would use it and name her company.

If I’ve heard of the author of the quote but think others may not have, I will, as in the case of Debbi Fields, add, “author,” “playwright,” or some other identification.

A different problem can arise if someone who is always quoted made the quote. Yes, Oprah, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk do have a lot to say, but I’d be cautious about quoting them. People might say, “Oh, another Oprah quote” and skip past it.

My rule of thumb here is: The more I see one name in my scanning of quotations, the less likely I am to use it.

I would also avoid using quotations by people who may have a polarizing effect, i.e., those who are on extreme ends of the political/social spectrum. This would depend on what I was writing.

Build a Quotations Collection

The other way you can work with quotations is to collect them so that you have many handy to put into your articles and books. File them in categories so that you can find them easily.

Sometimes you’ll get an unexpected bonus. A quotation may spark in you an idea for an article. You can deliberately activate this effect by going through your collection when you’ve run out of fresh ideas.

I close with this quotation:

A quotation in a speech, article or book is like a rifle in the hands of an infantryman. It speaks with authority.—Brendan Behan, Irish playwright

Pat Iyer is an editor and ghostwriter who helps authors shine. Contact her for a free consultation at patiyer.com.